Download here the boards needed to play Pente Grammai, Senet and Ludus Latrunculorum!

Games in Ancient History is a project created for the Classics and Ancient Civilisations Seminar for the Leiden University in 2018.

This website accompanies an exposition of three ancient games in the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden. It contains extra reading material and pictures.

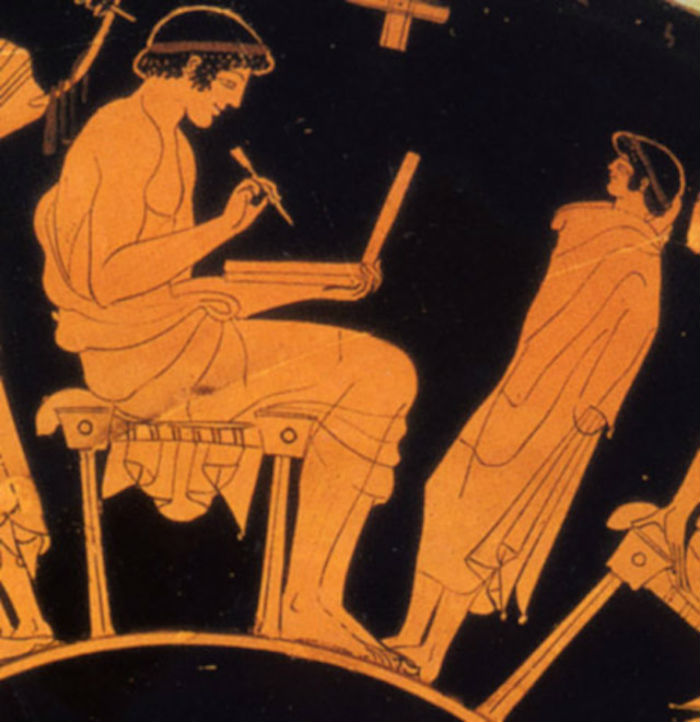

With respect to the Game of Twenty Squares our earliest known examples dates to the third millennium. Substantial amounts of our early archaeological evidence originate from funerary contexts, grave offerings are often better preserved than other objects. Many games have disintegrated because their boards were made from perishable material, such as textiles, leather, and wood, or simply drawn on the ground1. Within Southern Mesopotamia excellent instances were preserved at the Cemetery of Ur and in Iran, the Shar-I sokhta grave2. The game from the Cemetery of Ur is both our earliest and best-preserved example, dating to c.2600-2400 BCE at the time of the Sumerians in Mesopotamia (figure 1). As this well-known example was frequently studied it resulted in twenty squares alternate name, The Game of Ur. The board game top is richly decorated. However, the wooden base had rotted away by the time of excavation. In-situ it was possible to see that there was a drawer in which the playing pieces must have been kept. The Game of Ur is an opulent example and furthermore a grave good, yet many other examples exist to show it was game played in life amongst all. For example, the board-game has been found inscribed on the base of sculptures and on large clay blocks where ordinary, or non-elites would have played3. Thus, essentially twenty squares can be considered a national board game. At the turn of the second millennium the board underwent a change in the layout4 (figure 2). This innovation is first seen in Iran at two sites in the Kerman region in Iran at Tepe Yahya and Jiroft.

The board game has been found in many places in the Ancient Near East and it became increasingly popular throughout the second and first millennium leading fortunately to more archaeological evidence. Over one hundred examples are known from Iraq, Iran, Israel, Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, Cyprus, Egypt and Crete1. Hence, we know that the game crossed the borders of empires and city-states without going through any major changes in appearance. Accordingly, we can attest to cultural contacts across vast regions. If we consider that prestigious game boxes were among the luxury goods that circulated between the palatial societies of the Eastern Mediterranean as perhaps ‘gifts’ we can envision how this transmission may have taken place. Furthermore, thanks to stone examples we know that board games such as the game of twenty squares were part of the entertainment at the Assyrian court where international emissaries spent time2. Therefore, the game can be considered as a source of second millennium interaction with the Eastern Mediterranean. The ivory game of Enkomi is the western most example of the game and was found in Cyprus. In Egypt we have examples of the board game from the seventh century BCE onwards. Here it became associated with senat and both games are often found on either side of the same box. This is an excellent example of cultural transmission where variation is introduced with the result of multiple iterations of the game3. Transmission was not restricted to a spread from Assyria outwards. In Ur ten examples of ‘stick’ or long dice were found numbered to four. Such dice are not found anywhere else in Mesopotamia suggesting a possible external origin4.

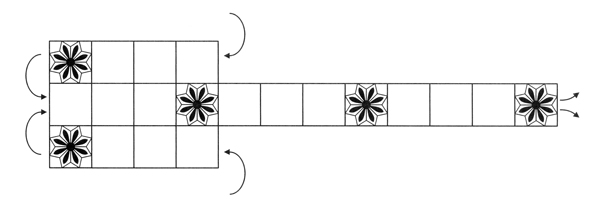

A cuneiform clay tablet was found dating to the 2nd century BCE on which rules were written by the scribe and Babylonian astronomer, Itti-Marduk-balāțu. The rules are a late and rather complicated version. This cuneiform document does not explain all the rules. Therefore, we must appreciate that the basic rules were assumed knowledge. The aim is to get your pieces safely off the board without the other player landing on them and knocking them off. It is essentially a race, or a war to get your pieces through the course first. There are five specially marked squares on the board that have rosettes on them. The rosette motif is omnipresent in the ancient Near East. It is the traditional symbol of Ištar, a female deity in ancient Mesopotamia. As goddess of war Ištar was well suited to oversee the metaphoric battle of a game, appearing as early as the third millennium BCE1.

Walter Crist, Alex de Voogt, Anne-Elizabeth Dunn-Vaturi did a systematic study of attributes and distribution of games. Their focus was on innovations in the game. They concluded that the more complex the game it will show lower rates of innovation over time1. They predicted that a simpler game will show higher rates of change over time and yet would diffuse more easily across socio-cultural boundaries. Twenty squares is an excellent example of this study. The older board games are nearly all homogenous. In our study we can conclude that it was Empire which helped diffuse the game, contained mostly between elites or traders and not between commoners from different ethnic groups2. Some of the earliest innovations appear in ca.1600 BCE in Egypt. Yet, in total there are fewer than twenty-five different configurations found. Despite going through generations, transmissions, cultural, linguistic and enemy borders very little innovation occurred in the game of twenty squares and it remained popular for a very long time.

Learn here how to play the Game!Games have always been a part of ancient Egyptian culture. The Egyptians had a variety of different games, played by all ages. The ancient Egyptians would even take board games with them in their graves. One of the best known ancient Egyptian board games is called Senet. Although the Egyptians did have paintings of themselves playing Senet in their tombs, no rulebook was left to us. Nevertheless, scholars have tried to recreate the game best as possible. It is thought that Senet had a religious meaning. The Egyptians believed that when you died, you passed through the underworld to the afterlife. In Senet the goal of the game is to pass through the underworld before the opposite player does. The name Senet literally means ‘passing’ in ancient Egyptian, making it known as ‘The Game of Passing’.

The first verse calls out to the different gods, hoping that they will permit the player to finish the thirty game spaces and win the game. The next verse listed here describes the first player’s desire to win the game: it shows the players intelligence and his conviction that his opponent will lose. The last verse showed here describes the end of the game: the first player will defeat his opponent, justifying his own soul.

An offering which the king gives to Ra, Atum, (to)

Wenennefer, the Lord of Justification, (to) the Thirty,

(to) Horus, Anubis, Toth, Shu, Maât, (to) the Crew of

theGreat Ones of the Good House, (to) Heka, Hu and Sia,

that they might permit me to enter the Council

Chamber of the Thirty,

so that I may become a God, as the thirty-first.

…

My heart is shrewd;

it is not forgetful.

My heart is clever in determining his play against me,

that is draughtsmen might turn backward to him.

His fingers are confused,

and his heart has removed itself from its place,

so that he does not know his response.

…

I shall approach my opponent,

I shall throw him into the Water,

that he might drown together with his draughtsmen.

‘You are justified’,

so Mehen will say to me

…

Did you know, that the most Senet board games were found not in Egypt, but in Cyprus. And did you know they probably did not learn the game from Egypt but from the Levant? The Levantines in their turn, learned the game from the Egyptians, who probably invented it.

Want to know more of Senet or other Egyptian board games? Read the following book: W. Christ, A.E. Dunn-Vaturi and A. de Voogt, Ancient Egyptians at Play: board games across borders (London 2016).

Pente Grammai was a backgammon-like boardgame from Greek Antiquity. It is one of the Greek boardgames from Antiquity we know of. The others are Polis and Diagrammismos. The Game is called Pente Grammai, or the game of the Five Lines, by modern scholars, for the name the Greek used for this game is not transmitted to us by the ancient sources we have. Although we cannot be completely sure about the rules and history of the game, we have literary (authors of the archaic and classical period and ancient scholars of later periods) and archaeological sources from which we can deduce some very valuable information about the game.

The earliest accounts of the game of Pente Grammai are from the centuries during which the game was played and they surround the proverb ‘moving away from the holy line’. The meaning of this proverb has been much debated. The first account is from Alcaeus, a poet of the early 6th century BCE.

Later accounts are from ancient scholars, such as Julius Pollux (2nd century CE) and Eustathius (12th century CE). Their accounts give us valuable information about the game: according to Pollux it was played on five lines and the middle line was ‘holy’, according to Eustathius the goal of the game is to reach the ‘holy line’.

The game was probably played in in the Archaic and Classical Greek periods (approximately 8th-4th century BCE). By the time Julius Pollux, a Greek scholar of the second century CE, wrote about the game, it must have been stopped being played and have become obscure.

For an impression of how the game was played, you can view the following video. Note however, that the rules are not the same as above and that no evidence is given for the proposed reconstruction in this video.

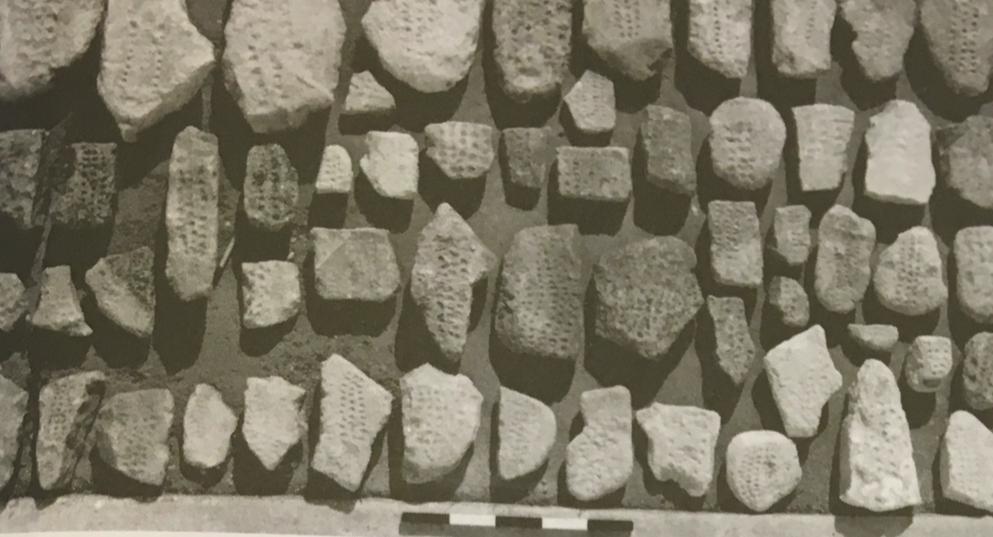

There are also several archaeological sources, such as models of gaming tables (see fig. 1). Several models of gaming-boards were found in Attica, for example in Athens. Similar boards were found for instance in Eretria on the island Euboea and on Delos. At Roman sites in Asia Minor, various gaming-boards with squares were found, so a variant of the game was probably played in Roman times as well.

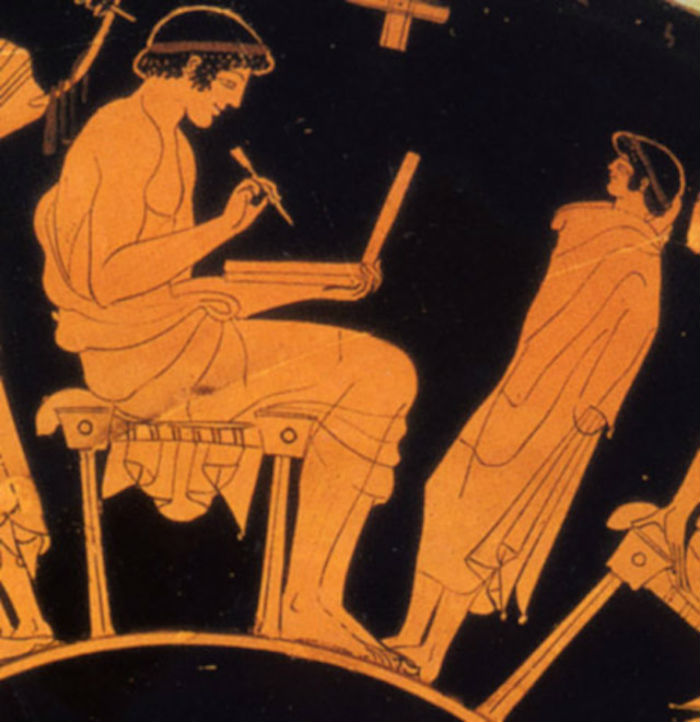

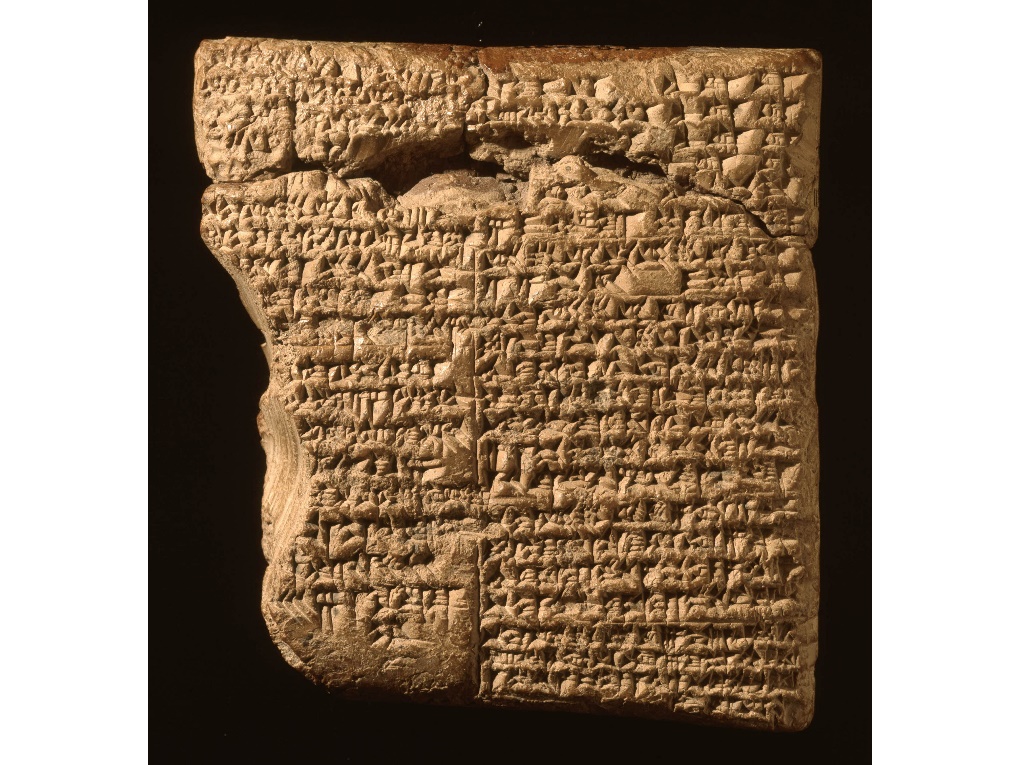

Objects on which the game is depicted have also been found, for example a painted vase which depicts Ajax and Achilles playing the game (see fig. 2) or an Etruscan mirror (see fig.3). On the Etruscan mirror, more lines can be seen, so larger variants of the game seem to have existed.

The ludus latrunculorum is a tactical game played by two players. The game is played on a board that consists of a number of rows and columns. We are using a board of eight by eight squares, but this could vary in ancient times. On this board two rows of black and white counters are used, like in a chess or chequers game. The counters are called latrones, they are often made of stone, glass or gemstones. The rules of this game are not certain, researchers are still debating about the right rulebook and maybe we will never know the correct rules. But as with all games, even in our time, everyone has his own variation (rulebooks are just so hard to understand!).

Te si forte iuuat studiorum pondere fessum

non languere tarnen lususque mouere per artem,

callidiore modo tabula uariatur aperta

calculus et uitreo peraguntur milite bella,

ut niueus nigros, nunc et niger alliget albos.

sed tibi quis non terga dedit? quis te duce cessit

calculus? aut quis non periturus perdidit hostem?

mille modis acies tua dimicat: ille petentem

dum fugit, ipse rapit; longo uenit ille recessu,

qui stellt in speculis; hic se committere rixae

audet, et in praedam uenientem decipit hostem;

ancipites subit ille moras similisque ligato

obligat ipse duos; hic ad maiora mouetur,

ut citus effrada prorumpat in agmina mandra

clausaque deiecto populetur moenia uallo.

interea sectis quamuis acerrima surgant

proelia militibus, plena tarnen ipse phalange

aut tantum pauco spoliata milite uincis,

et tibi captiua resonat manus utraque turba.

"When you are weary with the weight of your studies, if perhaps you are pleased not to be inactive but to Start games of skill, in a more clever way you vary the moves of your counters on the open board, and wars are fought out by a soldiery of glass, so that at one time a white counter traps blacks, and at another a black traps whites. Yet what counter has not fled from you? What counter gave way when you were its leader? What counter [of yours] though doomed to die has not destroyed its foe? Your battle line joins combat in a thousand ways: that counter, flying from a pursuer, itself makes a capture; another, which stood at a vantage point, comes from a position far retired; this one dares to trust itself to the struggle, and deceives an enemy advancing on its prey; that one risks dangerous traps, and, apparently entrapped itself, countertraps two opponents; this one is advanced to greater things, so that when the formation is broken, it may quickly burst into the columns, and so that, when the rampart is overthrown, it may devastate the closed walls. Meanwhile, however keenly the battle rages with cut-up soldiers, you conquer with a formation that is full, or bereft of only a few soldiers, and each of your hands rattles with its band of captives."

Ludus latrunculorum (from now on referred to as: ludus) is never wholly explained in a Latin text, no rulebooks have been found explaining every single aspect of the game. This makes the reconstruction of such an ancient game a challenge. In many Latin authors the game is incidentally mentioned, it is for example mentioned by Martial, by Varro and by Ovid in his Ars Amatoria and Tristia, but our greatest source is the Laus Pisonis. In the Laus Pisones of an unknown author a more elaborate explanation of the game is given in 18 lines (190-208). This passage of eighteen lines is, unfortunately, also open to different interpretations. The ludus is first specifically mentioned by Varro, but the game is thought to be much older.

Austin emphasizes that the ludus has no connection with chess as is suggested in earlier times, but the ludus is also a tactical game. The name simply means ‘the soldier-game’. As Richmond tells us we know from Varro and Festus that latro originally meant ‘a mercenary soldier’, ‘a bodyguard’ or ‘bandit’, and that the older poets used latro to mean miles, soldier. Ludus was 'the game of little soldiers' and this corresponds well with the military terminology constantly used by the author of the Laus Pisonis. The board of the game could vary in size, but Austin says that experiments have shown a 7x8 board makes such a game playable. The counters are called latrones, they are often made of stone or glass of different colours or sometimes even of jewels or gemstones. Hurschmann believes that twenty latrones were used in the game, but Austin suggests that the number of the counters varied according to the size of the board, which does make more sense.

Both in Rome and in widely distant areas of the Roman world archaeologists have found, incised on stone, the squared game boards that are used for playing the game. Together with these markings they found a very large number of small round disks and hemispheres, the counters. The game was for example also found in Roman sites in Britain with squared markings, generally showing 8x 8 squares, although the measurements vary. They found a lot of board games of ludus which suggests it was a popular game. Several of these finds have been made along the line of Hadrian's Wall.

he game was played by two players, which is implied in a text of Seneca (Dial. 9.14.7) where a prisoner is taken away to execution. He adjured his opponent not to claim falsely that he had been winning the game that was interrupted by the final summons. And the fact that black and white counters have been found, although others colours have been found as well, but not as often as black and white.

What are kids doing most of their time? They play! They do games with one another or they play with their toys. And so did the children in Roman times. Already two thousand years ago, children played with dolls or little soldiers and they even had yo-yo’s. What they however did most, was playing with marbles. They had marbles made of clay or stone, and sometimes even made of glass. Quite often they also simply used nuts. You could find nuts everywhere. Playing with nuts was so typical for children in those times, that when you became a grown-up, the Romans used to say that you ‘left your nuts behind’. By this they meant that the time of playing with nuts was over because you were no longer a child. We know, however, that the great emperor Augustus, even when he was a grown-up for many years, still played with marbles and nuts.

From excavations several ancient pictures are known of Roman children playing with marbles or nuts. They played whenever they were free from school, but especially during the festival of the Saturnalia, a kind of Roman Christmas. Then the Romans gave each other gifts and the children often got bags with marbles, or if you were not that rich, with nuts.

There were several different games Roman children used to play with nuts. The names of these games we know from ancient writers who wrote about them, such as the poet Ovid. We know approximately how these different games must have been played. We don’t know however the exact rules. Every child knew these rules, so why would you write them down!

A famous game is a game which the Romans called “Castle of Nuts”. There are several pictures carved in stone of Roman children playing this game. It probably was played as follows: first you make a triangle of three nuts and then you place one nut on top of these. This is called a tower. You can play the game with one tower, but you can, of course, also build several towers. Just like a castle. Next you decide who will begin. This was done by guessing whether someone had an even or uneven number of nuts in his closed hand. Just like nowadays we flip a coin. Then the game begins. From a fixed distance you throw a nut to destroy the tower or one of the towers. When you hit the tower you aim for, the nuts that are scattered from their place are yours. If you don’t hit the tower, it is the turn of the next child to try. The game ends when all the towers of the castle are completely destroyed. The winner is the one who has collected the largest number of nuts. Then you may be called triumphator. Just like a Roman general!

Senet wordt gespeeld met twee mensen op een spelbord met drie rijen van ieder 10 vakjes. Elke speler heeft ieder 5 pionnen die om en om op de eerste rij geplaatst worden. Het doel van het spel is om als eerste al je pionnen van het spelbord te krijgen. De looproute van de pionnen is in een z-vorm die begint in de linkerbovenhoek en eindigt in de rechteronderhoek. Het aantal vakjes dat een pion vooruit mag wordt bepaald aan de hand van 4 werpstokjes. Deze stokjes hebben één zwarte en één neutrale kant. Wanneer je aan de beurt bent, gooi je de werpstokjes in de lucht: hoe de stokjes landen bepaalt het aantal plaatsen dat één van je pionnen mag verzetten.

Als je je pion verzet naar een vakje waar al een pion van je tegenstander staan, verwisselen deze twee pionnen van plek: jij staat nu op de plek van je tegenstander en je tegenstander staat op de plek waar jouw pion stond. Als er twee of meer pionnen van een speler naast elkaar op het spelbord staan, zijn ze beschermd en kunnen ze niet verwisseld worden. Men moet dan een andere pion kiezen om mee te bewegen. Als er drie of meer pionnen van een speler naast elkaar op het spelbord staan, vormen ze een blokkade die niet gewisseld of gepasseerd kan worden door de tegenstander. Sommige spelvakjes (‘Huizen’ genoemd)zijn speciaal:

Pionnen op deze speciale vakjes mogen niet verwisseld worden. Wanneer je je worp met geen enkele van je pionnen uit kan voeren, verlies je de beurt en is je tegenstander aan de beurt.

De spelers zitten tegenover elkaar aan de smalle zijde van het bord, met de lijnen horizontaal voor zich. Beide spelers hebben 5 speelstenen. Deze worden nog van het spel gehouden. Deze stenen worden tijdens het spel, na het gooien van de dobbelsteen, tegen de klok in bewogen. Wanneer een steen op de laatste lijn van een zijde is, wordt deze langs de lijn naar de andere kant verschoven. Dit kan herhaald worden. Het doel is om alle stenen op de heilige lijn, de middelste lijn, aan de linkerkant van de speler, te laten eindigen.

Elke speler start in de hoek rechts onder van hem/haar. De stenen worden nog van het bord gehouden.

Rol de dobbelsteen om te beslissen wie begint. Daarna wisselen de spelers na elke beurt.

De speler die aan de beurt is, gooit de dobbelsteen en loopt vervolgens met een steen het aantal stappen dat de dobbelsteen aangeeft. Hij mag zelf kiezen welke steen hij wanneer verplaatst, maar mag maar met 1 steen lopen per worp.

Wanneer een speler twee of meer stenen op een lijn heeft, kan de andere speler niet op die lijn eindigen.

Wanneer een speler op een lijn eindigt waar één speler van de tegenstander op staat, moet de tegenstander met deze steen van het bord af en daarmee opnieuw beginnen vanaf de start.

De speler die als eerste de heilige lijn heeft bereikt met al zijn stenen wint het spel. De heilige lijn mag ook verlaten worden door de speler. Dit kan soms tactisch zijn. Hij moet dan wel de ronde opnieuw lopen en de steen weer laten eindigen op zijn kant van de heilige lijn.

Waar mogelijk moet een beurt uitgevoerd worden. Dit kan betekenen dat een steen van de heilige lijn moet worden verplaatst. Wanneer een speler geen enkele zet kan doen, verliest hij zijn beurt.

Ludus Latrunculorum is een tactisch spel dat door twee partijen/spelers gespeeld kan worden. Het doel van het spel is om zoveel mogelijk territorium te veroveren op het bord. De ene partij speelt met de zwarte stukken en de ander met de witte stukken.

De speelstukken kunnen zowel horizontaal als verticaal over het spelbord bewogen worden, diagonaal is niet mogelijk. Tijdens uw beurt kunt u een speelstuk bewegen over zoveel vakken als u wilt, zolang dit in één richting gebeurt, u kunt kiezen uit opwaarts/neerwaarts of links/rechts. Dus in één beurt kunt u het speelstuk niet één omhoog en twee naar rechts bewegen, het is of één omhoog of twee naar rechts. Het aantal vakken, waarover u kunt bewegen, wordt beperkt wanneer uw speelstuk geblokkeerd wordt door een ander speelstuk, uw eigen of die van uw tegenstander.

De eerste manier waarop speelstukken overwonnen kunnen worden is, wanneer ze door vijandige speelstukken omsingeld zijn. Dat betekent dat een zwart speelstuk, staande tussen twee witten, of andersom, overwonnen wordt wanneer het witte speelstuk als laatste in positie komt. Net zoals het bewegen van een speelstuk werkt dit zowel horizontaal, verticaal, maar niet diagonaal.

Bij de tweede manier om een speelstuk te slaan is het mogelijk om twee speelstukken tegelijkertijd te veroveren. Twee witte speelstukken staan op dezelfde rij, waarbij een zwart speelstuk zich begeeft naar de lege plek tussen deze twee stukken, het zwarte stuk overwint hier beide witte stukken.

Een speelstuk mag in bepaalde situaties niet bewegen. Als een speelstuk aangrenzend is aan twee vijandige speelstukken, bijvoorbeeld wanneer er zich een zwart speelstuk aan de linkerkant en een zwart speelstuk aan de onderkant bevindt van een wit speelstuk, dan mag het witte stuk niet meer bewegen. Het stuk mag weer bewegen wanneer een van de vijandige speelstukken wordt veroverd of verplaatst. Daarnaast kan het speelstuk ook bevrijd worden door je eigen stuk naast het belemmerde stuk neer te zetten aan een van de nog vrije kanten, hierdoor mag het belemmerde stuk weer bewegen.

Wanneer een groep stukken ingesloten is door vijandige speelstukken en er geen zet mogelijk is voor de omsingelde speler, dan zijn deze stukken overwonnen, maar als er nog een vrij speelstuk is van de omsingelde speler, dan gaat deze regel niet op.

Het spel is gewonnen wanneer alle speelstukken overwonnen zijn of wanneer de positie bereikt is waarin één van beide spelers geen zet meer kan doen (bijvoorbeeld doordat zijn/haar stukken ingesloten staan in de hoek), waarbij degene met het meeste territorium in bezit gewonnen heeft.